Social media influencer marketing: foundations, trends, and ways forward

The increasing use and effectiveness of social media influencers in marketing have intrigued both academic scholars and industry professionals. To shed light on the foundations and trends of this contemporary phenomenon, this study undertakes a systematic literature review using a bibliometric-content analysis to map the extant literature where consumer behavior, social media, and influencer marketing are intertwined. Using 214 articles published in journals indexed by the Australian Business Deans Council (ABDC), Chartered Association of Business Schools (CABS), and Web of Science (WOS) from 2008 to 2021, this study unpacks the articles, journals, methods, theories, themes, and constructs (antecedents, moderators, mediators, and consequences) in extant research on social media influencer marketing. Noteworthily, the review highlighted that the major research streams in social media influencer marketing research involve parasocial interactions and relationships, sponsorship, authenticity, and engagement and influence. The review also revealed the prominent role of audience-, brand-, comparative-, content-, influencer-, social-, and technology-related factors in influencing how consumers react to social media influencer marketing. The insights derived from this one-stop, state-of-the-art review can help social media influencers and marketing scholars and professionals to recognize key characteristics and trends of social media influencer marketing, and thus, drive new research and social media marketing practices where social media influencers are employed and leveraged upon for marketing activities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Influencer Marketing as a Counterstrategy to the Commoditization of Marketing Communications: A Bibliometric Analysis

Chapter © 2022

Influencer Marketing: Current Knowledge and Research Agenda

Chapter © 2021

What Do We Know About Influencers on Social Media? Toward a New Conceptualization and Classification of Influencers

Chapter © 2023

Explore related subjects

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Social media influencers are increasingly popular and affecting consumers’ attitudes, perceptions, preferences, choices, and decisions. Social media influencers are regular everyday people who have created an online presence from the grassroots level through their social media channel or page and, in the process, have created an extensive network of followers (Bastrygina and Lim [10]. In that sense, social media influencers are different than traditional celebrities or public figures, who rely on their existing careers (e.g., actors, singers, politicians) to become popular and exert influence [88].

Influencers first appeared in the early 2000s, and have since progressed from a home-based hobby to a lucrative full-time career. Influencer marketing has become so attractive that with the growing industry, there is an ever-growing set of social media users that aim to become an influencer. Influencers are now capitalizing on their popularity and visibility to further their career in mainstream media such as the film and television industry [1]. The segmentation of influencers is on the number of followers they have, whereby influencers can be classified as micro-, meso- and macro-influencers [44]. According to Lou and Yan [88], posts by influencers have two essential purposes from a marketing perspective: the first purpose is to increase the purchase intention of their followers, and the second purpose is to enhance their followers’ attractiveness and product knowledge. Influencers often curate posts with information and testimonials about the features of the product that they are promoting, which results in increased information value and product knowledge. In the process, they leverage and relay their attractiveness and aesthetic value through the use of sex appeal and posing [104].

Social media influencers have been defined by many scholars in numerous ways. Freberg et al. [44] characterized social media influencers as a new type of independent third-party endorser who shapes audience attitudes through blogs, tweets, and the use of other social media. Abidin [1] construed social media influencers as a form of microcelebrities who document their everyday lives from the trivial and mundane to the exciting snippets of the exclusive opportunities in their line of work, thereby shaping public opinion through the conscientious calibration of persona on social media. De Veirman et al. [28] defined social media influencers as people who built a large network of followers and are regarded as trusted tastemakers in one or several niches. Ge and Gretzel [45] denoted social media influencers as individuals who are in a consumer’s social graph and has a direct impact on the behavior of that consumer. More recently, Dhanesh and Duthler [30] described social media influencers as people who, through personal branding, build and maintain relationships with their followers on social media, and have the ability to inform, entertain, and influence their followers’ thoughts, attitudes, and behaviors. When these definitions are taken collectively and espoused through a marketing lens, social media influencers are essentially people who develop and maintain a personal brand and a following on social media through posts that intertwin their personality and lifestyle with the products (e.g., goods, services, ideas, places, people) that they promote, which can influence the way their followers behave (e.g., attitudes, perceptions, preferences, choices, decisions), positively (e.g., purchase) or negatively (e.g., do not purchase).

Social media influencers, as digital opinion leaders, participate in self-presentation on social media. They form an identity by creating an online image using a rich multimodal narrative of their everyday personal lives and using it to attract a large number of followers [59]. Most critical to their success is the influencer-follower relationship [1], which future follower behavior (e.g., interaction, purchase intention) is dependent upon [13], [37], [126]. Indeed, social media influencers are often perceived to be credible, personal, and easily relatable given their organic rise to fame [28], [31], [104].

In collaborations between brands and social media influencers, the role of a social media influencer is to act as a brand ambassador by designing sponsored content for the brand to convey and enhance its brand image and brand name [104], and to drive brand engagement and brand loyalty [72]. Such content is often curated by social media influencers, as independent third-party endorsers, by sharing their experiences and lives in relation to the brand through pictures, texts, stories, hashtags, and check-ins, among others [28]. Indeed, social media influencers are highly sought after by brands because they have established credibility with their followers as a result of their expertise, which allow them to exert influence on the decision-making of their followers [60]. Moreover, influencer marketing through social media can provide opportunities to influencers and their followers to contribute to the co-creation of the brand’s image on social media [88].

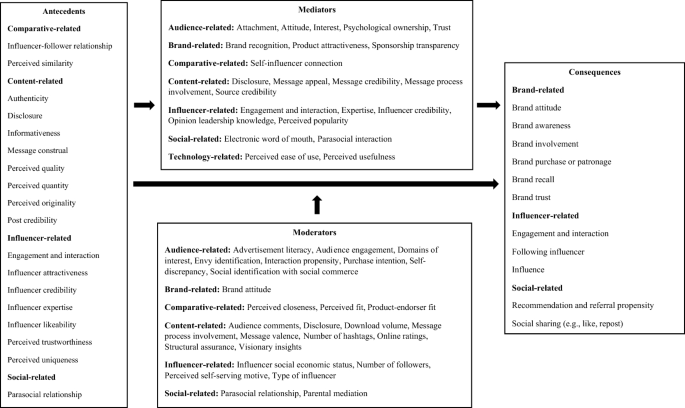

With the growing importance of influencer marketing and the popularity of social media influencers, various brands have started promoting their products with the help of social media influencers in an attempt to influence consumers to behave in desired ways (e.g., forming positive brand attitudes and encourage product brand purchases) [104]. However, consumer behavior is highly complex [81], and increasing inconsistency has been noted in the effectiveness of this medium [124]. Thus, it is essential to understand the factors (i.e., antecedents) underpinning consumer decision making (i.e., consequences or decisions) toward brands promoted by social media influencers, including the factors (i.e., mediators and moderators) responsible for the inconsistency in consumer responses. In this regard, attempts to consolidate extant knowledge in the field is arguably relevant to address the extant gap and needs of marketing scholars and professionals interested in social media influencer marketing.

In recognition of the growing influence of social media influencers and influencer marketing in consumer decision making, this study aims to provide a one-stop, state-of-the-art overview of the articles, journals, methods, theories, themes, and constructs (antecedents, moderators, mediators, and consequences) relating to social media influencer marketing using a systematic review of articles in the area from 2008 to 2021. Though a recent review on social media influencers was conducted by Vrontis et al. [124], the present review remains warranted because the existing review only considered a small sample of 68 articles published in journals indexed in the Chartered Association of Business Schools Academic Journal Guide, and thus, cannot holistically encapsulate the state of the field. Indeed, the insights and the integrative framework resulting from their review was relatively lean, which can be attributed to the sample limitations that the authors had imposed for their review. The same can be said about another recent review by Bastrygina and Lim [10], which considered only 45 articles in Scopus that narrowly focused only on the consumer engagement aspect of social media influencers. To overcome these limitations, the present review will consider a more inclusive search and inclusion criteria while upholding to the highest standards of academic quality by relying on a broader range of indexing sources. The motivation of the present review is also in line with the call by Lim et al. [86] and Paul et al. [98] for new reviews that address the shortcoming of existing reviews in order to redirect research in the area onto a clearer and more refined path for progress. In addition, the present review adopts a bibliometric-content analysis to consolidate current findings, uncover emerging trends and extant gaps, and curate a future agenda for social media influencer marketing. Noteworthily, the rigorous multi-method review technique (i.e., the combination of a bibliometric analysis and a content analysis) adopted for the present review is in line with the recommendation of Lim et al. [86] to facilitate a deeper dive into the literature, and thus, enabling the curation of a richer depiction of the nomological network characterizing the field [94], in this case, the field of social media influencer marketing. In doing so, this study contributes to answering the following research questions (RQs):

- RQ1. What is the publication trend of social media influencer marketing research, and which are the key articles?

- RQ2. Where is research on social media influencer marketing published?

- RQ3. How has social media influencer marketing research been conducted?

- RQ4. What are the theories that can be used to inform social media influencer marketing research?

- RQ5. What are the major themes of social media influencer marketing research?

- RQ6. What are the constructs (i.e., antecedents, mediators, moderators, and consequences) employed in social media influencer marketing research?

- RQ7. Where should social media influencer marketing be heading towards in the future?

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. The next section provides an account of the methodology used in the research, followed by the findings and conclusions of the study in subsequent sections.

2 Methodology

This study conducts a multi-method systematic literature review on social media influencer marketing using a bibliometric-content analysis in line with the recommendation of Lim et al. [86] and recent systematic literature reviews (e.g., Kumar et al. [64]. The assembling, arranging, and assessing techniques stipulated in the Scientific Procedures and Rationales for Systematic Literature Reviews (SPAR-4-SLR) protocol by Paul et al. [98] to carry out a systematic literature review are also adopted and explained in the next sections.

2.1 Assembling

Assembling relates to the identification (i.e., review domain, research questions, source type, and source quality) and acquisition (i.e., search mechanism and material acquisition, search period, search keywords) of articles for review. In terms of identification, the review domain relates to social media influencer marketing, but within the subject areas of business management, social sciences, hospitality, tourism, and economics due to their immediate relevance to the review domain, and thus, articles in other subject areas such as computer science, engineering, medical, and mathematics, which are peripheral to the review domain, were not considered. Next, the research questions underpinning the review pertain to the articles, journals, methods, theories, themes, and constructs in the field and were presented in the introduction section. Only journals were considered as part of source type as they are the main sources of academic literature that have been rigorously peer reviewed Nord & Nord, [96]. The source quality was inclusive yet high quality, whereby articles published in journals indexed in the Australian Business Deans Council (ABDC), Chartered Association of Business Schools (CABS), and Web of Science (WOS) were included. In terms of acquisition, the search mechanism and material acquisition relied on the WOS database, which is connected to myriad publishers such as Emerald, Sage, Springer, Taylor and Francis, and Wiley. The search period starts from 2008 and ends in 2021. The year 2008 was selected as the starting year because it was the year that the concept of influencer was first introduced by Kiss and Bichler [63], and thus, a review staring from 2008 can provide a more accurate and relevant account of the extant literature on influencer marketing, particularly from the lenses of consumers and social media influencers. The end year 2021 was selected because it is the most recent full year at the time of search—a practice in line with Lim et al. [83]. The search keywords—i.e., “consumer behavio*” (truncation technique), “social media,” “influencer,” and “marketing”—were curated through brainstorming and endorsed by disciplinary experts in marketing and methodological experts in review studies. In total, 320 articles were returned from the search, but 17 articles were removed as they were related to engineering, mathematics, and medicine, which resulted in only 303 articles that were retrieved for the arranging stage.

2.2 Arranging

Arranging relates to the organization (i.e., organizing codes) and purification (i.e., exclusion and inclusion criteria) of articles returned from the search. In terms of organization, the content of articles was coded based on the key focus of each research question: journal title, method, theory, and construct (antecedent, mediator, moderator, consequence). The bibliometric details of the articles were also retrieved and organized accordingly in this stage. In terms of purification, 89 articles were eliminated as they were not published in journals indexed by ABDC and CABS, with the rest of the 214 articles included for review.

2.3 Assessing

Assessing relates to the evaluation (i.e., analysis method, agenda proposal method) and reporting (i.e., reporting conventions, limitations, and sources of support) of articles under review. In terms of evaluation, a bibliometric analysis and a content analysis were conducted.

For the bibliometric analysis, the Bibliometrix package in R studio software [4] was used to conduct (1) a performance analysis to reveal the publication trend as well as the key articles and journals (RQ1 and RQ2), and (2) a science mapping to uncover the major themes in the field (RQ5) in line with the bibliometric guidelines by Donthu et al. [32]. With regards to science mapping, a triangulation technique was adopted in line with the recommendation of Lim et al. [86] using:

- 1. co-citation using PageRank, wherein the major themes are revealed through the clustering of articles that are most cited by highly-cited articles,

- 2. bibliographic coupling, wherein the major themes are revealed through the clustering of articles that cite similar references, and

- 3. keyword co-occurrence, wherein the major themes are revealed through the clustering of author specified keywords that commonly appear together [32], [64].

For the content analysis, the within-study and between-study literature analysis method by Ngai [95] was adopted (RQ3, RQ4, and RQ6). The within-study literature analysis evaluates the entire content of the article (e.g., theoretical foundation, methodology, constructs), whereas the between-study literature analysis consolidates, compares, and contrasts information between two or more articles. The future research agenda proposal method is predicated on the expert evaluation of a trend analysis by the authors (RQ7). In terms of reporting, the conventions for the outcomes reported include figures, tables, and words, whereas the limitations and sources of support are acknowledged at the end.

3 Findings

The findings of the review are organized based on the research questions (RQs) of the study: articles, journals, methods, theories, themes, and constructs.

3.1 Articles

The first research question (RQ1) deals with the publication trend and key articles of social media influencer marketing research.

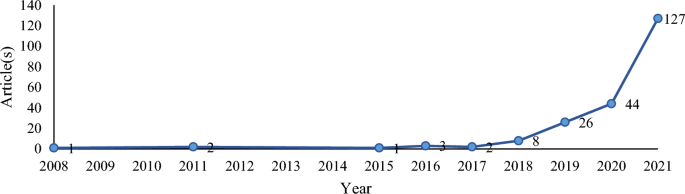

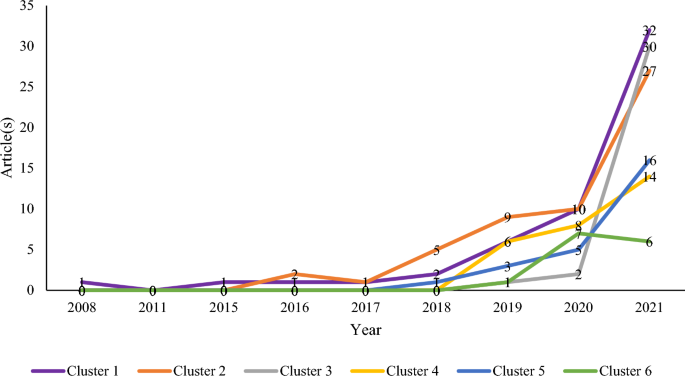

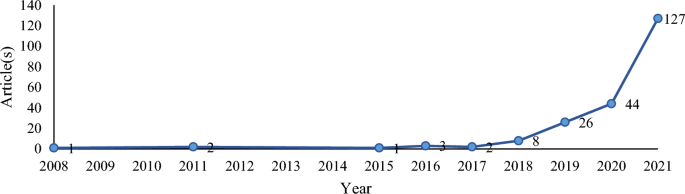

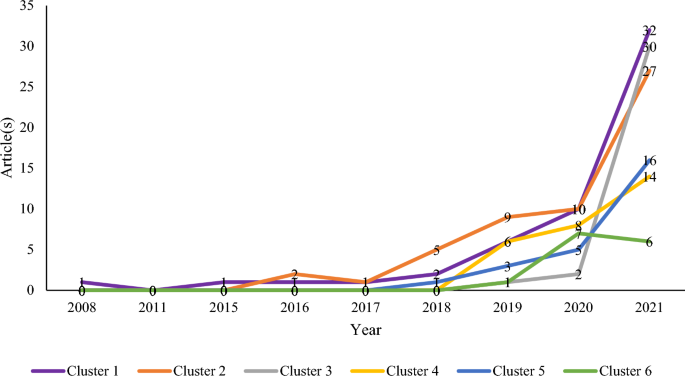

Figure 1 indicates that research on social media influencer marketing began to flourish 10 years (i.e., 2018 onwards) after the concept of was introduced in 2008 [63]. This implies that interest in social media influencer marketing is fairly recent (i.e., within the last five years at the time of analysis), wherein its stratospheric growth appears to have coincided with that of highly interactive and visual content-focused social media such as Instagram (e.g., Instagram Stories feature launched in December 2017) [17] and TikTok (e.g., international launch in September 2017) [129]. The growth of triple-digit publications observed in 2021 during the COVID-19 pandemic is especially noteworthy as it signals the importance of social media influencer marketing in the new normal and reaffirms past observations of an acceleration in technology adoption [77], [79].

Table 1 presents the top articles on social media influencer marketing. The most cited article is De Veirman et al.’s [28] (464 citations), which focused on social media influencer marketing using Instagram and revealed the impact of the number of followers and product divergence on brand attitudes among the followers of social media influencers. The burgeoning interest on Instagram as seen through this most cited article despite its recency corroborates the earlier observation on the stratospheric growth in research interest on highly interactive and visual content-focused social media. The top-cited articles in recent years demonstrate increasing research interest in comparative studies (e.g., celebrity versus social media influencer endorsements, [104],Instagram versus YouTube; [108], as well as review studies (e.g., Hudders et al., [48], [124], albeit the latter being limited (e.g., small review corpus, niche review focus) and thus reaffirming the necessity and value of the present review.

4.2 Topical perspective

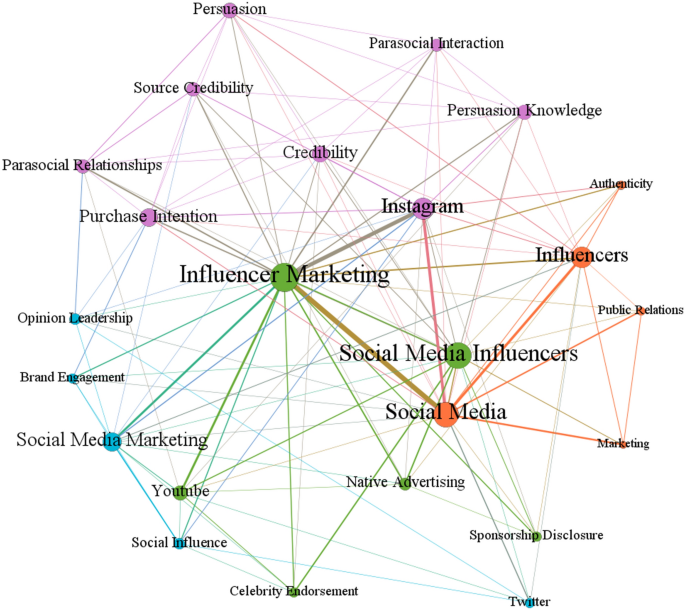

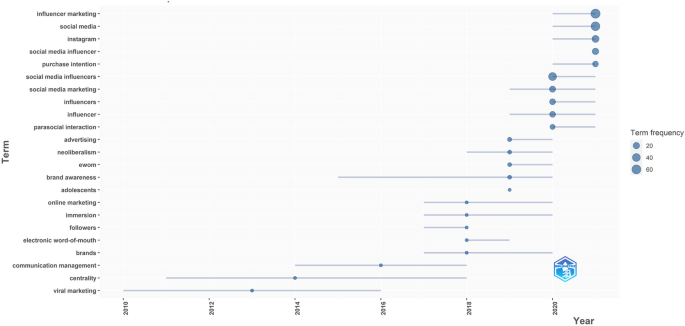

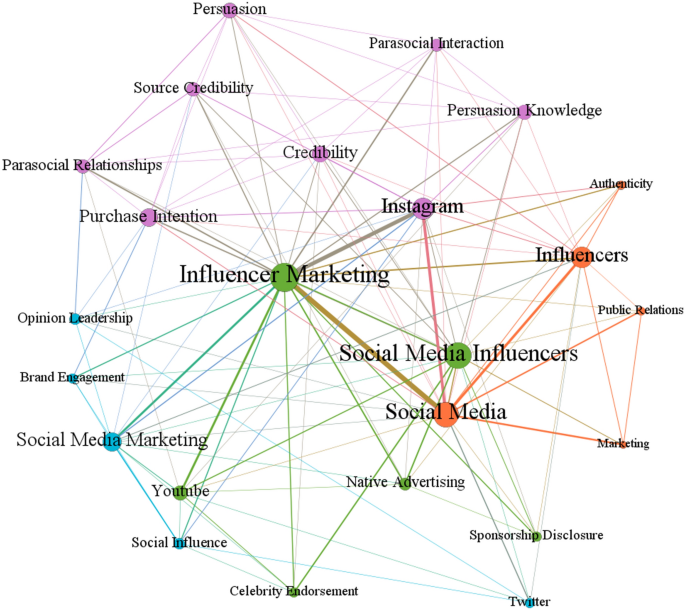

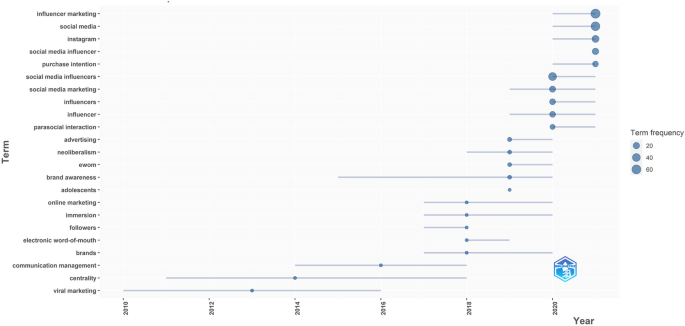

The productivity of topical research in social media influencer marketing has evolved over the years (Fig. 5). Noteworthily, the extant literature on social media influencer marketing has been largely predicated on “communication management”, “centrality”, and “viral marketing” up to 2018. Newer research has nonetheless made a stronger and more explicit connection to “influencer marketing” and “social media”, with “Instagram” emerging as the most prominent social media in the field. The transmission of “eWOM” or “electronic word-of-mouth” and how this translates into “parasocial interaction” or “immersion” between “social media influencers” and “followers” has taken center stage alongside “online marketing” and “social media marketing” considerations such as “advertising”, “brands”, “brand awareness”, and “purchase intention” from a “neoliberalism” perspective.

Notwithstanding the trending topics in social media influencer marketing revealed by the trend analysis, it is clear that new research focusing on new phenomena is very much required. For example, new social media platforms such as Clubhouse and TikTok have been extremely popular platforms for social media influencers in recent years, and thus, future research should also consider exploring social platforms other than Instagram. Furthermore, the proliferation of augmented and virtual realities remains underexplored for social media influencer marketing. The rebranding of Facebook to Meta is a signal of the future rise of the metaverse. New research in this direction focusing on new-age technologies for social media influencer marketing should provide new knowledge-advancing and practice-relevant insights into contemporary trends and realities that remain underrepresented in the literature. Similarly, the diversity and evolution of social media followers also deserve further attention in light of accelerated technology adoption by societies worldwide in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and the new normal [77], as well as the changing nature of generational cohorts in the society [79].

5 Conclusion

The importance of consumerism for business survival and growth albeit in a more authentic, meaningful, and sustainable way [76] along with the increasing use of digital media such as social media [82] have led to the proliferation of social media influencer marketing and its burgeoning interest among academics and professionals [10], [124]. This was evident in the present study, wherein the consumer behavior perspective of social media influencer marketing took center stage. Using the SPAR-4-SLR protocol as a guide, a bibliometric-content analysis as a multi-method review technique, and a collection of 214 articles published in 87 journals indexed in ABDC, CABS, and WOS as relevant documents for review, this study provides, to date, the most comprehensive one-stop state-of-the-art overview of social media influencer marketing. Through this review, this study provides several key takeaways for theory and practice and additional noteworthy suggestions for future research.

5.1 Theoretical contributions and implications

From a theoretical perspective, this study provides two major takeaways for academics.

First, the review indicates that most articles on social media influencer marketing published in journals indexed in ABDC, CABS, and WOS were not guided by an established theory, as only 94 (43.93%) out of the 214 articles reviewed were informed by theories (e.g., persuasion knowledge theory, social learning theory, source credibility theory, theory of planned behavior). This implies that most articles relied on prior literature only to explain their study’s theoretical foundation, which may be attributed to a lack of awareness on the possible theories that may be relevant to their study. In fact, a similar review on the topic albeit with a relatively smaller sample of articles (i.e., 68 articles only) due to protocol limitations (i.e., CABS-indexed journals only) had acknowledged the issue but unfortunately failed to deliver a collection of theories informed by prior research [124]. In this vein, this study hopes to address this issue as it has revealed 46 different theories that were employed in prior social media influencer marketing research, which can be used to ground future research in the area. Furthermore, the list of theories can be used to justify the novelty of future research where a new theory is applied. In addition, future studies can take inspiration from the manifestation of theories emerging from multiple theoretical perspectives, such as the social influencer value model and the social-mediated crisis communication theory informed by the media and sociological theoretical perspectives, to develop new theories in the field, which may be challenging but certainly possible [81]. Alternatively, future studies can consider theoretical integration by using two or more theories in a single investigation, which can reveal richer insights on the phenomenon (e.g., which theoretical perspective is more prominent or which factors from which theoretical perspective yield strong impacts and therefore warrant investment prioritization).

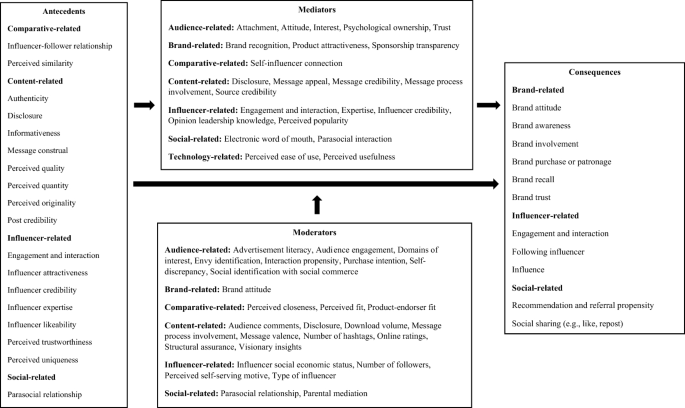

Second, the review shows that social media influencer marketing research does not have to be limited to a simple direct antecedent-consequence relationship or the multiply of such relationships. Instead, research in the area can benefit from testing the mediating and moderating effects of various factors to enrich the insights derived from their study. Interestingly, the review reveals that antecedents can also play the role of mediators (e.g., engagement and interaction) and moderators (e.g., parasocial relationship) and vice versa, which implies that the conditions in research design setup are fundamental to the conclusions made about the consequences of social media influencer marketing [75], which can take the form of consumer responses to the brand (e.g., brand purchase or patronage), the influencer (e.g., following influencer), and the community (e.g., recommendation, social sharing). In total, seven categories in the form of audience-, brand-, comparative-, content-, influencer-, social-, and technology-related factors that could manifest as antecedents, mediators, and moderators were revealed. Noteworthily, the comparative-related factors such as perceived closeness, perceived fit, perceived similarity, self-influencer connection, and product-endorser fit transcended across multiple categories (e.g., audience and influencer, brand and influencer), which indicate the promise of social media influencer marketing as a research context suitable for the development of new factors to describe consumer behavior of a comparative nature. Indeed, comparative-related factors is, to the best knowledge of the authors, a new categorization that has not been revealed by prior systematic literature reviews, and thus, represent a key contribution to the literature that should be noted in future research and reviews. Moreover, the mapping of constructs in Fig. 3 and their counts in Tables 8, 9, 10, and 11 provide useful starting points to identify the extant gaps in prior research (e.g., brand-related factors remain underexplored as moderators, comparative-related factors remain underexplored as mediators) and to inform the direction of future research accordingly. Finally, the constructs and their associated categories revealed can also be compared and contrasted in future investigations to delineate the difference in impact between constructs of different categories, and when paired with appropriate theories, can provide stronger grounds for managerial recommendations to brands and influencers interested to leverage off the benefits of social media influencer marketing to attract and persuade desired consumer behavior.

5.2 Managerial contributions and implications

From a managerial perspective, this study provides two major takeaways for brands and influencers.

First, the review indicates that brands indirectly influence consumers through influencers—that is to say, the strategy of brands engaging in influencer marketing on social media places influencers at the forefront, with brands taking a backseat in that strategy. This was evident from the literature review, where brand-related antecedents were absent; instead, the influence of brands manifests in the form of mediators (e.g., brand recognition, product attractiveness, sponsorship transparency) and moderators (e.g., brand attitude). In that sense, it is important that brands identify and engage with influencers strategically, particularly those who are perceived to be attractive, credible, engaging and interactive, experts, a good fit for their products, likeable, opinion leaders, popular, trustworthy, unique, and without overly self-serving motives in order to encourage desired consumer behavior toward their brands (e.g., brand purchase and patronage, brand trust), as revealed by the review herein.

Second, the review reveals that social media influencers directly influence consumer behavior toward the brands they promote (e.g., brand attitude, brand awareness, brand involvement, brand recall, brand trust), the influencers themselves (e.g., follower, influence), and the social media community at large (e.g., recommendation, social sharing). In particular, the content that influencers curate on social media can affect how consumers respond to these stakeholders. The review indicates that such content should be authentic, credible, informative, original, and transparent (disclosure). The message appeal and message process involvement are also important mediators to strengthen the influencer’s ability to encourage desired consumer behavior among their followers (e.g., positive audience, brand, influencer, and social behavior), whereas audience comments, assurance, hashtags, insights, and volume of posts can moderate or nullify the potential desired impact that influencers could elicit from their followers on social media. Indeed, the importance of electronic word of mouth, parasocial interaction, and perceptions of closeness and fit have also been highlighted through the review. Importantly, when promoting to kids and youth, it is essential that influencers consider what parents would think about their posts, as parental mediation was observed to occur in the review.

5.3 Review limitations and future review directions

From a review perspective, this study acknowledges three major limitations that can inform the curation of future reviews.

First, the systematic literature review herein does not capture article performance (i.e., citations) because it was mainly interested in unpacking the articles, journals, theories, methods, and content (themes, constructs) underpinning existing research on social media influencer marketing, and it kept in mind the space limitation of the journal. Notwithstanding the comprehensive and rigorous insights revealed using the SPAR-4-SLR protocol, future reviews may wish to pursue an impact analysis, which can lead to rich insights pertaining to article performance (e.g., difference in citations [e.g., total citations, average citations per year, h-index, g-index] between papers with and without theory, using empirical and non-empirical methods, or across different methods and thematic categories).

Second, the systematic literature review herein encapsulates only a qualitative evaluation of the constructs in existing social media influencer marketing research. To build on the insights herein, future reviews may wish to pursue a meta-analytical review, where a meta-analysis involving the antecedents, mediators, moderators, and consequences revealed in Tables 8, 9, 10, and 11 in this review (in the short run) or unveiled in future reviews (in the long run) is performed. Such an endeavor should also provide finer-grained insights on conflicting findings and provide a resolution to such findings in the same study.

Third, the systematic literature review herein focuses only on the consumer behavior perspective of social media influencer marketing, which is mainly due to the maturity of research from this perspective [98], as seen through the number of articles available for review (i.e., 214 articles) under a rigorous protocol (i.e., the SPAR-4-SLR protocol). Moving forward, future reviews may wish to pursue a systematic review of social media influencer marketing from the business and industrial perspective, wherein the impact of influencer marketing on social media for business and industrial brands in general and across different industries are reviewed and reported.

References

- Abidin, C. (2016). Visibility labour: Engaging with Influencers’ fashion brands and# OOTD advertorial campaigns on Instagram. Media International Australia,161(1), 86–100. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Araujo, T., Neijens, P. C., & Vliegenthart, R. (2017). Getting the word out on Twitter: The role of influentials, information brokers and strong ties in building word-of-mouth for brands. International Journal of Advertising,36(3), 496–513. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Argyris, Y. A., Wang, Z., Kim, Y., & Yin, Z. (2020). The effects of visual congruence on increasing consumers’ brand engagement: An empirical investigation of influencer marketing on Instagram using deep-learning algorithms for automatic image classification. Computers in Human Behavior,112, 106443. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Aria, M., & Cuccurullo, C. (2017). bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. Journal of Informetrics,11(4), 959–975. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Arora, A., Bansal, S., Kandpal, C., Aswani, R., & Dwivedi, Y. (2019). Measuring social media influencer index-insights from Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services,49, 86–101. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Audrezet, A., de Kerviler, G., & Moulard, J. G. (2020). Authenticity under threat: When social media influencers need to go beyond self-presentation. Journal of Business Research,117, 557–569. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Aw, E., & Chuah, S. (2021). Stop the unattainable ideal for an ordinary me! Fostering parasocial relationship with social media influencers: The role of self-discrepancy. Journal of Business Research, 132(7), 146–157.

- Balaji, M. S., Jiang, Y., & Jha, S. (2021). Nanoinfluencer marketing: How message features affect credibility and behavioral intentions. Journal of Business Research, 136, 293–304.

- Barry, J. M., & Gironda, J. (2018). A dyadic examination of inspirational factors driving B2B social media influence. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice,26(1–2), 117–143. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Bastrygina, T., & Lim, W. M. (2023). Foundations of consumer engagement with social media influencers. International Journal of Web Based Communities.

- Belanche, D., Casalo, L. V., Flavian, M., & Ibanez-Sanchez, S. (2021). Building influencers’ credibility on Instagram: Effects on followers’ attitude and behavioral responses toward the influencer. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 61, 102585.

- Berne-Manero, C., & Marzo-Navarro, M. (2020). Exploring how influencer and relationship marketing serve corporate sustainability. Sustainability,12(11), 4392. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Boerman, S. C. (2020). The effects of the standardized Instagram disclosure for micro-and meso-influencers. Computers in Human Behavior,103, 199–207. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Boerman, S. C., & Van Reijmersdal, E. A. (2020). Disclosing influencer marketing on YouTube to children: The moderating role of para-social relationship. Frontiers in Psychology,10, 3042. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Breves, P. L., Liebers, N., Abt, M., & Kunze, A. (2019). The perceived fit between Instagram influencers and the endorsed brand: How influencer–brand fit affects source credibility and persuasive effectiveness. Journal of Advertising Research,59(4), 440–454. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Britt, R. K., Hayes, J. L., Britt, B. C., & Park, H. (2020). Too big to sell? A computational analysis of network and content characteristics among mega and micro beauty and fashion social media influencers. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 20, 1–25.

- Cakebread, C. (2017). Instagram updates its Stories feature, copying Snapchat again. Insider. Available at https://www.insider.com/instagram-added-two-news-features-to-stories-2017-12

- Campbell, C., & Farrell, J. R. (2020). More than meets the eye: The functional components underlying influencer marketing. Business Horizons,63(4), 469–479. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Casalo, L. V., Flavian, C., & Ibanez-Sanchez, S. (2018). Influencers on Instagram: Antecedents and consequences of opinion leadership. Journal of Business Research,117, 510–519. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Chae, J. (2018). Explaining females’ envy toward social media influencers. Media Psychology,21(2), 246–262. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Chatterjee, P. (2011). Drivers of new product recommending and referral behaviour on social network sites. International Journal of Advertising,30(1), 77–101. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Chen, K., Lin, J.-S., & Shan, Y. (2021). Influencer marketing in China: The roles of parasocial identification, consumer engagement, and inferences of manipulative intent. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 20(6), 1436–1448.

- Chetioui, Y., Benlafqih, H., & Lebdaoui, H. (2020). How fashion influencers contribute to consumers’ purchase intention. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal,24(3), 361–380. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Cooley, D., & Parks-Yancy, R. (2019). The effect of social media on perceived information credibility and decision making. Journal of Internet Commerce,18(3), 249–269. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Croes, E., & Bartels, J. (2021). Young adults’ motivations for following social influencers and their relationship to identification and buying behavior. Computers in Human Behavior, 124, 106910.

- Cuevas, L. M., Chong, S. M., & Lim, H. (2020). Influencer marketing: Social media influencers as human brands attaching to followers and yielding positive marketing results by fulfilling needs. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services,55, 102133. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- De Cicco, R., Iacobucci, S., & Pagliaro, S. (2020). The effect of influencer–product fit on advertising recognition and the role of an enhanced disclosure in increasing sponsorship transparency. International Journal of Advertising.,40(5), 733–759. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- De Veirman, M., Cauberghe, V., & Hudders, L. (2017). Marketing through Instagram influencers: The impact of number of followers and product divergence on brand attitude. International Journal of Advertising,36(5), 798–828. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- De Vries, E. L. (2019). When more likes is not better: The consequences of high and low likes-to-followers ratios for perceived account credibility and social media marketing effectiveness. Marketing Letters,30(3), 275–291. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Dhanesh, S. G., & Duthler, G. (2019). Relationship management through social media influencers: Effects of followers’ awareness of paid endorsement. Public Relations Review,45(3), 101765. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Djafarova, E., & Rushworth, C. (2017). Exploring the credibility of online celebrities’ Instagram profiles in influencing the purchase decisions of young female users. Computer in Human Behavior,68, 1–7. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Donthu, N., Kumar, S., Mukherjee, D., Pandey, N., & Lim, W. M. (2021). How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research,133, 285–296. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Duan, J. (2021). The impact of positive purchase-centered UGC on audience’s purchase intentions: Roles of tie strength, benign envy and purchase type. Journal of Internet Commerce. Google Scholar

- Enke, N., & Borchers, N. S. (2019). Social media influencers in strategic communication: A conceptual framework for strategic social media influencer communication. International Journal of Strategic Communication,13(4), 261–277. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Erdogan, B. Z. (1999). Celebrity endorsement: A literature review. Journal of Marketing Management,15(4), 291–314. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Erz, A., Marder, B., & Osadchaya, E. (2018). Hashtags: Motivational drivers, their use, and differences between influencers and followers. Computers in Human Behavior,89, 48–60. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Evans, N. J., Hoy, M. G., & Childers, C. C. (2018). Parenting “YouTube natives”: The impact of pre-roll advertising and text disclosures on parental responses to sponsored child influencer videos. Journal of Advertising,47(4), 326–346. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Evans, N. J., Phua, J., Lim, J., & Jun, H. (2017). Disclosing Instagram influencer advertising: The effects of disclosure language on advertising recognition, attitudes, and behavioral intent. Journal of Interactive Advertising,17(2), 138–149. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Farivar, S., Wang, F., & Yuan, Y. (2021). Opinion leadership vs. para-social relationship: Key factors in influencer marketing. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 59, 102371.

- Feng, Y., Chen, H., & Kong, Q. (2020). An expert with whom I can identify: The role of narratives in influencer marketing. International Journal of Advertising.,40(7), 972–993. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Ferchaud, A., Grzeslo, J., Orme, S., & Lagroue, J. (2018). Parasocial attributes and YouTube personalities: Exploring content trends across the most subscribed YouTube channels. Computers in Human Behavior, 80, 88–96.

- Fink, M., Koller, M., Gartner, J., Floh, A., & Harms, R. (2020). Effective entrepreneurial marketing on Facebook – A longitudinal study. Journal of Business Research, 113, 149–157.

- Folkvord, F., Roes, E., & Bevelander, K. (2020). Promoting healthy foods in the new digital era on Instagram: An experimental study on the effect of a popular real versus fictitious fit influencer on brand attitude and purchase intentions. BMC Public Health,20(1), 1–8. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50.

- Freberg, K., Graham, K., McGaughey, K., & Freberg, L. A. (2011). Who are the social media influencers? A study of public perceptions of personality. Public Relations Review,37, 90–92. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Ge, J., & Gretzel, U. (2018). Emoji rhetoric: A social media influencer perspective. Journal of Marketing Management,34(15–16), 1272–1295. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Gupta, Y., Agarwal, S., & Singh, P. B. (2020). To study the impact of Instafamous celebrities on consumer buying behavior. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal,24(2), 1–13. Google Scholar

- Harrigan, P., Daly, T., Coussement, K., Lee, J., Soutar, G., & Evers, U. (2021). Identifying influencers on social media. International Journal of Information Management, 56, 102246.

- Hudders, L., De Jans, S., & De Veirman, M. (2021). The commercialization of social media stars: A literature review and conceptual framework on the strategic use of social media influencers. In N. S. Borchers (Ed.), Social Media Influencers in Strategic Communication. New York: Routledge.

- Hughes, C., Swaminathan, V., & Brooks, G. (2019). Driving brand engagement through online social influencers: An empirical investigation of sponsored blogging campaigns. Journal of Marketing,83, 78–96. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Hu, H., Zhang, D., & Wang, C. (2019). Impact of social media influencers’ endorsement on application adoption: A trust transfer perspective. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal,47(11), 1–12. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Jang, W., Kim, J., Kim, S., & Chun, J. W. (2020). The role of engagement in travel influencer marketing: The perspectives of dual process theory and the source credibility model. Current Issues in Tourism,24(17), 2416–2420. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Jiménez-Castillo, D., & Sánchez-Fernández, R. (2019). The role of digital influencers in brand recommendation: Examining their impact on engagement, expected value and purchase intention. International Journal of Information Management,49, 366–376. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Jin, S. A. A., & Phua, J. (2014). Following celebrities’ tweets about brands: The impact of twitter-based electronic word-of-mouth on consumers’ source credibility perception, buying intention, and social identification with celebrities. Journal of Advertising,43(2), 181–195. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Jin, S. V., & Ryu, E. (2019). Celebrity fashion brand endorsement in Facebook viral marketing and social commerce: Interactive effects of social identification, materialism, fashion involvement, and opinion leadership. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal,23(1), 104–123. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Jin, S. V., Muqaddam, A., & Ryu, E. (2019). Instafamous and social media influencer marketing. Marketing Intelligence & Planning,37(5), 567–579. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Jin, S. V., & Ryu, E. (2020). Instagram fashionistas, luxury visual image strategies and vanity. Journal of Product & Brand Management,29(3), 355–368. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Jun, S., & Yi, J. (2020). What makes followers loyal? The role of influencer interactivity in building influencer brand equity. Journal of Product & Brand Management,29(6), 803–814. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Kay, S., Mulcahy, R., & Parkinson, J. (2020). When less is more: The impact of macro and micro social media influencers’ disclosure. Journal of Marketing Management,36(3–4), 248–278. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Khamis, S., Ang, L., & Welling, R. (2017). Self-branding, ‘micro-celebrity’ and the rise of social media influencers. Celebrity Studies,8(2), 191–208. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Ki, C.-W.C., & Kim, Y.-K. (2019). The mechanism by which social media influencers persuade consumers: The role of consumers’ desire to mimic. Psychology & Marketing,36(10), 905–922. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Ki, C., Cuevas, L. M., Chong, S. M., & Lim, H. (2020). Influencer marketing: Social media influencers as human brands attaching to followers and yielding positive marketing results by fulfilling needs. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 55, 102133.

- Kim, D. Y., & Kim, H. Y. (2020). Influencer advertising on social media: The multiple inference model on influencer-product congruence and sponsorship disclosure. Journal of Business Research.,130, 405–415. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Kiss, C., & Bichler, M. (2008). Identification of influencers—Measuring influence in customer networks. Decision Support Systems,46(1), 233–253. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Kumar, S., Lim, W. M., Sivarajah, U., & Kaur, J. (2022a). Artificial intelligence and Blockchain integration in business: Trends from a bibliometric-content analysis. Information Systems Frontiers,25(2), 871–896. Google Scholar

- Kumar, S., Sahoo, S., Lim, W. M., & Dana, L. P. (2022b). Religion as a social shaping force in entrepreneurship and business: Insights from a technology-empowered systematic literature review. Technological Forecasting and Social Change,175, 121393. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lahuerta-Otero, E., & Cordero-Gutiérrez, R. (2016). Looking for the perfect tweet. The use of data mining techniques to find influencers on twitter. Computers in Human Behavior,64, 575–583. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lee, J. E., & Watkins, B. (2016). YouTube vloggers influence on consumer luxury brand perceptions and intentions. Journal of Business Research, 69(12), 5753–5760.

- Lee, J. A., & Eastin, M. S. (2020). I like what she’s # endorsing: The impact of female social media influencers’ perceived sincerity, consumer envy, and product type. Journal of Interactive Advertising,20(1), 76–91. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lee, S., & Kim, E. (2020). Influencer marketing on Instagram: How sponsorship disclosure, influencer credibility, and brand credibility impact the effectiveness of Instagram promotional post. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing, 11(3), 232–249.

- Lee, S., & Kim, E. (2020). Influencer marketing on Instagram: How sponsorship disclosure, influencer credibility, and brand credibility impact the effectiveness of Instagram promotional post. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing,11(3), 232–249. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Li, X., & Feng, J. (2022). Engaging social media influencers in nation branding through the lens of authenticity. Global Media and China, 7(2), 219–240.

- Lim, X., Radzol, J. M., Cheah, J. H., & Wong, M. W. (2017). The impact of social media influencers on purchase intention and the mediation effect of customer attitude. Asian Journal of Business Research,7(2), 19–36. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lim, W. M. (2018a). Demystifying neuromarketing. Journal of Business Research,91, 205–220. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lim, W. M. (2018b). What will business-to-business marketers learn from neuro-marketing? Insights for business marketing practice. Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing,25(3), 251–259. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lim, W. M. (2021a). Conditional recipes for predicting impacts and prescribing solutions for externalities: The case of COVID-19 and tourism. Tourism Recreation Research,46(2), 314–318. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lim, W. M. (2021b). Empowering marketing organizations to create and reach socially responsible consumers for greater sustainability. In J. Bhattacharyya, M. K. Dash, C. Hewege, M. S. Balaji, & W. M. Lim (Eds.), Social and sustainability marketing: A casebook for reaching your socially responsible consumers through marketing science. New York: Routledge. Google Scholar

- Lim, W. M. (2021c). History, lessons, and ways forward from the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Quality and Innovation,5(2), 101–108. Google Scholar

- Lim, W. M. (2022a). The sustainability pyramid: A hierarchical approach to greater sustainability and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals with implications for marketing theory, practice, and public policy. Australasian Marketing Journal,30(2), 142–150. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lim, W. M. (2022b). Ushering a new era of Global Business and Organizational Excellence: Taking a leaf out of recent trends in the new normal. Global Business and Organizational Excellence,41(5), 5–13. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lim, W. M., & Rasul, T. (2022). Customer engagement and social media: Revisiting the past to inform the future. Journal of Business Research,148, 325–342. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lim, W. M., & Weissmann, M. A. (2023). Toward a theory of behavioral control. Journal of Strategic Marketing,31(1), 185–211. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lim, W. M., Ahmad, A., Rasul, T., & Parvez, M. O. (2021a). Challenging the mainstream assumption of social media influence on destination choice. Tourism Recreation Research,46(1), 137–140. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lim, W. M., Ciasullo, M. V., Douglas, A., & Kumar, S. (2022a). Environmental social governance (ESG) and total quality management (TQM): A multi-study meta-systematic review. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2022.2048952ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lim, W. M., Kumar, S., & Ali, F. (2022b). Advancing knowledge through literature reviews: ‘What’, ‘why’, and ‘how to contribute.’ The Service Industries Journal,42(7–8), 481–513. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lim, W. M., Rasul, T., Kumar, S., & Ala, M. (2022c). Past, present, and future of customer engagement. Journal of Business Research,140, 439–458. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lim, W. M., Yap, S. F., & Makkar, M. (2021b). Home sharing in marketing and tourism at a tipping point: What do we know, how do we know, and where should we be heading? Journal of Business Research,122, 534–566. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lin, H. C., Bruning, P. F., & Swarna, H. (2018). Using online opinion leaders to promote the hedonic and utilitarian value of products and services.Business Horizons,61(3), 431–442. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lou, C., Ma, W., & Feng, Y. (2020). A sponsorship disclosure is not enough? How advertising literacy intervention affects consumer reactions to sponsored influencer posts. Journal of Promotion Management,27(2), 278–305. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lou, C., & Yuan, S. (2019). Influencer marketing: How message value and credibility affect consumer trust of branded content on social media. Journal of Interactive Advertising,19(1), 58–73. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lou, C., Tan, S. S., & Chen, X. (2019). Investigating consumer engagement with influencer-versus brand-promoted ads: The roles of source and disclosure. Journal of Interactive Advertising,19(3), 169–186. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Luoma-aho, V., Pirttimäki, T., Maity, D., Munnukka, J., & Reinikainen, H. (2019). Primed authenticity: How priming impacts authenticity perception of social media influencers. International Journal of Strategic Communication,13(4), 352–365. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Magno, F., & Cassia, F. (2018). The impact of social media influencers in tourism. Anatolia,29(2), 288–290. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Martinez-Lopez, F. J., Anaya-Sanchez, R., Giordano, M. F., & Lopez-Lopez, D. (2020). Behind influencer marketing: Key marketing decisions and their effects on followers’ responses. Journal of Marketing Management,36(7–8), 579–607. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Mccracken, G. (1989). Who is the celebrity endorser? Cultural foundations of the endorsement process. Journal of Consumer Research, 16(3), 310–321.

- Mukherjee, D., Lim, W. M., Kumar, S., & Donthu, N. (2022). Guidelines for advancing theory and practice through bibliometric research. Journal of Business Research,148, 101–115. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Ngai, E. W. T. (2005). Customer relationship management research (1992–2002): An academic literature review and classification. Marketing Intelligence and Planning,23, 582–605. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Nord, J. H., & Nord, G. D. (1995). MIS research: Journal status assessment and analysis. Information and Management, 29(1), 29–42.

- Ohanian, R. (1990). Construction and validation of a scale to measure celebrity endorsers’ perceived expertise, trustworthiness, and attractiveness. Journal of Advertising, 19(3), 39–52.

- Paul, J., Lim, W. M., O’Cass, A., Hao, A. W., & Bresciani, S. (2021). Scientific procedures and rationales for systematic literature reviews (SPAR-4-SLR). International Journal of Consumer Studies,45(4), O1–O16. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Pick, M. (2020). Psychological ownership in social media influencer marketing. European Business Review,33(1), 9–30. Google Scholar

- Piehler, R., Schade, M., Sinnig, J., & Burmann, C. (2021). Traditional or ‘instafamous’ celebrity? Role of origin of fame in social media influencer marketing. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 30(4), 408–420.

- Pittman, M., & Abell, A. (2021). More trust in fewer followers: Diverging effects of popularity metrics and green orientation social media influencers. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 56(1), 1–13.

- Reinikainen, H., Munnukka, J., Maity, D., & Luoma-aho, V. (2020). ‘You really are a great big sister’—Parasocial relationships, credibility, and the moderating role of audience comments in influencer marketing. Journal of Marketing Management,36(3–4), 279–298. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Saima, & Khan, M. A. (2020). Effect of social media influencer marketing on consumers’ purchase intention and the mediating role of credibility. Journal of Promotion Management,27(4), 503–523. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Sánchez-Fernández, R., & Jiménez-Castillo, D. (2021). How social media influencers affect behavioural intentions towards recommended brands: The role of emotional attachment and information value. Journal of Marketing Management,37(11–12), 1123–1147.

- Schouten, A. P., Janssen, L., & Verspaget, M. (2020). Celebrity versus influencer endorsements in advertising: The role of identification, credibility, and product-endorser fit. International Journal of Advertising,39(2), 258–281. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Shan, Y., Chen, K. J., & Lin, J. S. (2020). When social media influencers endorse brands: the effects of self-influencer congruence, parasocial identification, and perceived endorser motive. International Journal of Advertising, 39(1), 1–21.

- Shin, E., & Lee, J. E. (2021). What makes consumers purchase apparel products through social shopping services that social media fashion influencers have worn? Journal of Business Research, 132, 416–428.

- Silvera, D., & Austad, B. (2004). Factors predicting the effectiveness of celebrity endorsement advertisements. European Journal of Marketing, 38(11/12), 1509–1526.

- Sokolova, K., & Kefi, H. (2020). Instagram and YouTube bloggers promote it, why should I buy? How credibility and parasocial interaction influence purchase intentions. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services,53, 101742. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Sokolova, K., & Perez, C. (2021). How parasocial relationships, and watching fitness influencers, relate to intentions to exercise. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 58, 102276.

- Stubb, C., & Colliander, J. (2019). This is not sponsored content—The effect of impartiality disclosure and e-commerce landing pages on consumer responses to social media influencer posts. Computers in Human Behavior,98, 210–222. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Stubb, C., Nyström, A.-G., & Colliander, J. (2019). Influencer marketing: The impact of disclosing sponsorship compensation justification on sponsored content effectiveness. Journal of Communication Management,23(2), 109–122. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Su, B., Wu, L., Chang, Y., & Hong, R. (2021). Influencers on social media as references: Understanding the importance of parasocial relationships. Sustainability, 13, 1–19.

- Sun, J., Leung, X., & Bai, B. (2021). How social media influencer’s event endorsement changes attitudes of followers: the moderating effect of followers’ gender. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 33(7), 2337–2351.

- Tafesse, W., & Wood, B. (2021). Followers’ engagement with Instagram influencers: The role of influencers’ content and engagement strategy. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 58, 102303.

- Taillon, B. J., Mueller, S. M., Kowalczyk, C. M., & Jones, D. N. (2020). Understanding the relationships between social media influencers and their followers: The moderating role of closeness. Journal of Product & Brand Management,29(6), 767–782. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Till, B., & Busler, M. (2000). Matching products with endorsers: Attractiveness versus expertise. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 15(6), 576–586.

- Torres, P., Augusto, M., & Matos, M. (2019). Antecedents and outcomes of digital influencer endorsement: An exploratory study. Psychology & Marketing,36(12), 1267–1276. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Trivedi, J. P. (2018). Measuring the comparative efficacy of an attractive celebrity influencer vis-à-vis an expert influencer—A fashion industry perspective. International Journal of Electronic Customer Relationship Management,11(3), 256–271. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Trivedi, J., & Sama, R. (2020). The effect of influencer marketing on consumers’ brand admiration and online purchase intentions: An emerging market perspective. Journal of Internet Commerce,19(1), 103–124. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Uzunoglu, E., & Kip, S. M. (2014). Brand communication through digital influencers: Leveraging blogger engagement. International Journal of Information Management,34(5), 592–602. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Valsesia, F., Proserpio, D., & Nunes, J. C. (2020). The positive effect of not following others on social media. Journal of Marketing Research,57(6), 1152–1168. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- van Reijmersdal, E. A., & van Dam, S. (2020). How age and disclosures of sponsored influencer videos affect adolescents’ knowledge of persuasion and persuasion. Journal of Youth and Adolescence,49(7), 1531–1544. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- van Reijmersdal, E. A., Rozendaal, E., Hudders, L., Vanwesenbeeck, I., Cauberghe, V., & van Berlo, Z. M. (2020). Effects of disclosing influencer marketing in videos: An eye tracking study among children in early adolescence. Journal of Interactive Marketing,49, 94–106. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Vrontis, D., Makrides, A., Christofi, M., & Thrassou, A. (2021). Social media influencer marketing: A systematic review, integrative framework and future research agenda. International Journal of Consumer Studies,45(4), 617–644. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Weismueller, J., Harrigan, P., Wang, S., & Soutar, G. N. (2020). Influencer endorsements: How advertising disclosure and source credibility affect consumer purchase intention on social media. Australasian Marketing Journal,28(4), 160–170. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Wojdynski, B. W., Bang, H., Keib, K., Jefferson, B. N., Choi, D., & Malson, J. L. (2017). Building a better native advertising disclosure. Journal of Interactive Advertising,17(2), 150–161. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Woodcock, J., & Johnson, M. R. (2019). Live streamers on Twitch.tv as social media influencers: Chances and challenges for strategic communication. International Journal of Strategic Communication,13(4), 321–335. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Xu, X., & Pratt, S. (2018). Social media influencers as endorsers to promote travel destinations: An application of self-congruence theory to the Chinese Generation Y. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing,35(7), 958–972. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Yang, Y., & Goh, B. (2020). Timeline: TikTok's journey from global sensation to Trump target. Reuters. Available at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-tiktok-timeline-idUSKCN2510IU

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.